The Poetry Centre is excited to announce the winners of our 2020 competition, which this year was judged by poet Fiona Benson. Two top prizes of £1,000 were on offer in a competition that seeks to celebrate the great diversity of poetry being written in English all over the world.

2020 Winners and shortlist

Poems were submitted in two categories: EAL category (open to all poets over 18 years of age who speak English as an Additional Language), and Open category (open to all poets over 18 years of age). We were delighted to receive a record number of entries this year by 740 poets from nearly 60 different countries. You can find the list of winners and the shortlisted poets below, as well as the judge's report. Read the winning poems by clicking on the links.

Fiona Benson won an Eric Gregory Award in 2006 and was a Faber New Poet in 2009. Her pamphlet was Faber New Poets 1 in the Faber New Poets series, whilst her debut collection, Bright Travellers, won both the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize and the Seamus Heaney Centre for Poetry Prize for First Full Collection in 2015. Her latest collection, Vertigo & Ghost, was published by Jonathan Cape in 2019, shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize, and won the Forward Prize for Best Collection and the Roehampton Prize. Fiona lives in rural Devon with her husband and two daughters, and is currently working on a commission of poetry celebrating insects with Arts & Culture at the University of Exeter. Hear Fiona read from her most recent book.

Very many thanks indeed to all the poets who entered and to our judge.

he said I was a peach

couldn’t see him didn’t know the crocus

pollen on my toes would be a dowry

black earth gulped my legs my shoulders

covered my head my footprints with itself

the taste of aquifers stone forests

mantle I am dead I reasoned

through dusted lashes knelt

somewhere head bowed informed I am

to be comfort for a mud king

with strange pets

I gripped a grass blade still

bright with my own kissed breath

there was a wed-ing of sorts

my stomach and other parts surveyed

to fathom my capacity

hung from my feet to siphon sunlight

blood pressed for foxglove poisons

panned for gold molecules

then began the drinking a feast of carrion

the maltworm king crowed his huge

knowledge of human weakness how fitting you are mine

he cracked for the price of your hunger

how fitting he the corpse lord mistook silence

for surrender and half-sober stirs

face down on his throne mound bound

under my foot my heel in grey cheekflesh

and at my word forfeits all but

everything of his even the dogs

by Katie Byford

for other reasons. Practice makes enough.

Clichés ride on thermals like strains of the song

you’ve got to search for the hero inside yourself.

Learn to duck and leave. In your mind’s ear

go to the hospice where your dad stayed

for respite care then curtains, not curtains,

he died. Don’t say angels, every last one

of those people, peaceful, don’t say

the birds sang their hearts out, lovely garden,

fragrant pink roses or he had new pyjamas

buttoned all the way like a little boy.

Say you watched a plane fly over and imagined it

packed with divorced guinea pig enthusiasts

heading somewhere wet. Say they wore gaiters

and read badly written blockbusters,

with stabbings they won't have seen coming.

Say there was a doctor in a green jumper

so thin you could see her bra and she was crouching

beside your dad’s bed. Say she was pregnant

but you couldn’t tell until she stood up,

which happened after she had recited a list

of possible happinesses for your dad

in a soft voice, whilst slowly stroking his arm.

Say his pyjama sleeve was rolled up

past the elbow and the palm of his hand

was upturned, reminding you of a clean ashtray

or Christ. Say she stroked upwards, asking

would you like to play scrabble? then down,

or do the Sudoku together? Fancy a baguette

with ham, and a sliced tomato?

Wagner’s ring cycle on headphones?

Or maybe you’d like a whisky with ice? Don’t say

if your own children turn out half as kind

as the people who work in hospices,

yours will have been a life well-lived, job done

or that you miss your dad more than ever

all these years on. Say he chose a whisky

and some pork scratchings. Say the pregnant doctor

poured a treble. Don’t call the ice rocks.

by Vanessa Lampert

I am 7, or 6, or 5 & have not yet learned the language of grief or the

sound of a body falling into silence. People die everyday in our country,

but it is not our country; it is someplace faraway in our TV where

there are bombs, fire dancing on bodies, schoolchildren without desks

& 9pm news that are about stolen billions & men in boats saying

they tire of drinking oil with water. Already knew the square root

of 16 is 4 & that in ‘67 our people went to war, but I had not wandered

yet into the ambits of pain. Mourners tore soft songs from their souls

with their tongues & their wails bounced off the walls, off my little

body & sat at my feet in shards—the crowd waits upon Christ,

seeking bread from his hands, then blood from his side—

They whisper that I do not cry. That I am dry-eyed. That I do not

tear my hair apart to clear the path for the departing dead.

Me; dry driftwood of a miracle dancing with careless abandon while

the boatswain, arms flailing, tries to rouse God from sleep. I think

that moment was when I began to look back at the call of names

belonging to another, walk into dreams not mine & pluck hibiscuses

in fields where vultures make the trespassers-will-be-shot signs sway.

In a hospital in Ibadan, a man clutched to his chest the grief of another

man & his eyes closed to give him a taste of lightlessness. I understand

a man fainting at the sight of a headless mangled body that left blood in

the wake of the stretcher but I did not know, until the doctor ran tests,

that grief has beautiful names & psychic trauma is one of them.

A boy I knew would run across the sky every night to harvest a star for

every woman he loved & each of them always left with a part of him in

her handbag or on her; just between her hair & her weave, until he gave

the only part of him left to a rope from his ceiling fan, stardust spilling

from his mouth, & each swing said something like grief has many robes

& one of them is heartbreak but I am not sure—the cops cordoned off the

area do not cross but grief is a borderless country to which you can get

trafficked/ into which you can wander & as you drive on, you won’t notice

the signs trespassers will get shot/no stopping/welcome because you are

too happy to know you have been here before, too amnesic to remember

that grief is a man of many garbs & one of them is joy.

by Onyekachi Iloh

what stops collective pain. Throat as dry as that dangling

catheter, dry as that slim, cold saline pack—which unlike life

is about to be replaced. We know only so much warm flesh

the earth embrace, only so much pressure her ribs can

endure. There is a shame in remembering that I slept well

that night. Numbers blinking like andromeda. Numbers swimming

on the screen. Sixty per thirty, seventy five percent. Numbers jumping

up, numbers drowning, numbers I keep wanting to go the opposite way.

Fifty per twenty, forty three percent. This means you’re half-breathing

Mother, this means half of your lung gives up while the other’s foolish. Poor

half-lung, doesn’t know we’ve settled the score last night. They said

the body can’t betray itself, yet God can stab anywhere without hearing

the word betrayal. Forty per twenty, thirty eight percent. Let’s just leave,

skip the long beep. Skip the Yasin. People flipping your worldly, jiggly

remains in a metal desk. The urge that I have to kiss the bruises on

your chest. On your lower back a burgundy crust, a gaping dark basin.

I mutter a muted Allahu Akbar. God you are so Great. When I say this

it means hypnosis. It means faith. Like batons, life is being passed on

by the dead. A quiet poem flutters in your palm. Like orphans, we—

by Dianty Ningrum

it's about the dogs, she says

she sits and she isn't mother

but helpless nonetheless, a divorce

is as much about leaving as it is

about what you take with you

what you can carry and it's the dogs

they need homes, you can't leave

dogs, it goes against the soul

so you leash them with soft hands

you direct them into kind-natured

killing until whatever you are

whatever even mattered, is that

your house has become twilight

a shade of desperation and they

say Cerberus was once a snake

coiled around his master's ankles

you see, so many things can be called

dogs, love for instance when it's sweaty

and pawing your cheek for attention

or when it springs up unawares and

catches you, in shackles for hands

eager and panting, as it spills

like a pomegranate at your feet

by Milla van der Have

- 'Border' by Elena Croitoru

- 'Ars Poetica' by Claire Miranda Roberts

- 'My Grandfather Ready for the Club, 1960' by Jonathan Edwards

- 'On the occasion of my son gumming his first drumstick' by Janine Bradbury

- 'My Mother’s Hair' by Kim Moore

- '2020: With all this death around' by Krystelle Bamford

- 'Slip' by Amelia Loulli

- 'Son, for Thetis' by Katie Byford

- 'Spoilt / spilt / split' by Sara Levy

- 'A Strange Creature Named Anxiety' by Ian Walker

- 'The Touch' by Ali Lewis

- 'Sheep Chorus, Lisheegan' by Mícheál McCann

- 'Deep-Sea Diver' by Kevin Smith

- 'The Angel Speaks to Vladimir' by Millie Guille

Judging this competition has been brutal. So many scandalously good and beautiful poems were submitted. To reach the winning six, I had to set aside poems I loved ferociously – god-touched buckets swarming with minute life, hospitals that talk, kerosene kings, anxiety-pangolins, a glass vase in shark-fin smithereens, a grandpa dancing like a duck – and shortlisting them felt obscene; reader-writer, forgive me.

Reading the EAL entries was a particularly humbling experience. I felt that the umbrella term ‘EAL’ was – rather like the term ‘world music’ – hopelessly inadequate. The poems carried with them such vast hinterlands of cultural tradition and musicality, such freights of influence and erudition; it was an enrichment and a blessing to read them.

From the many gifts of the EAL submissions, I kept circling back to four poems. The EAL winner, ‘Grief Is a Man With Many Gifts’, grapples with trauma, and straddles two home countries – one of dubious safety, and one in which fire dances on bodies. There is a sincerity and porousness to this poem – a rushing-in of images, and a gorgeous momentum – as it moves between hibiscus and vultures, the harvesting of stars and suicide, which is utterly compelling. Its final line is breath-taking as the speaker remembers that “grief is a man of many garbs & one of them is joy.” It is that rare and wonderful thing: a poem that deepens and expands with every reading.

In second place, ‘Mother won’t know who signs her DNR’ evokes a beeping, lit, hospitalised death with hypnotic lucidity, and enacts an uneasy acquiescence to mortality and God. The hospital rhythms and numbers both propel and rupture the poem as life and faith stutter and assert, stutter and assert themselves. Rarely have I felt in the presence of such a reckoning.

The special commendation is ‘my mother asks me how to leave my father’ – a perfect dance of language and imagery embodying the pain of separation. Any one of these three EAL poems would have been a worthy winner of any damn competition.

I deduce that the winner of the open competition, ‘Appetit, for Persephone’ is also responsible for the shortlisted ‘Son, for Thetis’, and to be honest, I had a hard time choosing between the two. Both are powerful, strange, virtuosic retellings of classical myth. I loved how Achilles’ call drifting down to his sea-goddess mother through her cold, grey kingdom is “a warm strain softening the frozen kelp, like piss”. In the end I chose ‘Appetit, for Persephone’ as my winner for the stark, uncanny beauty of its language and imagery ('informed I am // to be comfort for a mud king / with strange pets'), its acute details ('the crocus / pollen on my toes') and its discomfiting sensual realm – we sink with Persephone, tasting 'aquifers stone forests' in our mouths as we fall through black earth. The poem is a strange and wondrous haunting.

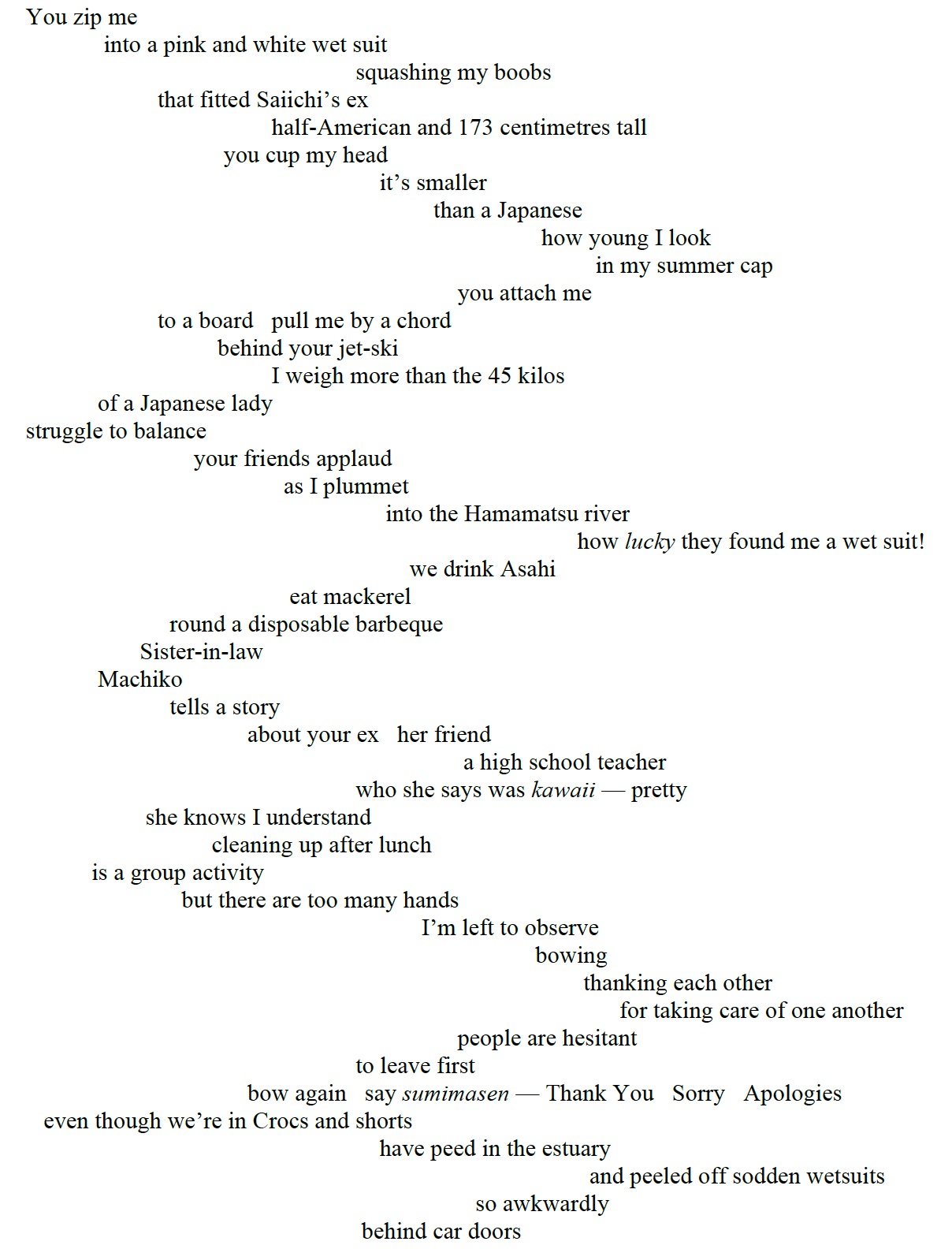

‘How to avoid clichés’, second place poem, is again a story of parental death, told with great tenderness, and with a fluidity of sound and language that I admired tremendously (even if I could have done without the guinea pigs!). Its palliative care doctor in her green jumper is such a gorgeous embodiment of human kindness that I hope she lives in my head for ever. The specially recommended ‘Wakeboarding, in Hamamtsu’ made me snicker in recognition of the appalling social awkwardness of the situation, something its layout re-enacts in its jolting half lines; its economic, wry retelling and acute sensitivity make for a comic, cringing masterpiece.

The twenty shortlisted and winning poems gathered here on my desk now, make a beautiful anthology. They contain such a wealth of human stories, and sing so gloriously in their language. They have brought me great joy in this time of Covid, even if they are often tender and wrung-out and sad. Under a government that waves its hand vaguely in the direction of the Arts and suggests that perhaps we ‘retrain’, these poems feel like a forcefield of empathy, defiance, resistance, skill, love and humanity. In this we live.

Fiona Benson